By Michael RosenthalSpecial to ESPN.com

By Michael RosenthalSpecial to ESPN.com

A buzzing throng packed a back room at the old Forum in Los Angeles in the fall of 1992 for the unveiling of a future superstar. Oscar De La Hoya, impossibly good-looking and bursting with charisma, was holding a news conference to announce the beginning of his professional career a few months after bringing home Team USA's only boxing gold medal from the Barcelona Olympics.

He had yet to enter a professional ring but already was a can't-miss prospect, the complete package, the pressure-packed "next Sugar Ray Leonard."

He had yet to enter a professional ring but already was a can't-miss prospect, the complete package, the pressure-packed "next Sugar Ray Leonard."

Fourteen years later, De La Hoya, now 33, can look back on his career with great pride. He has won world titles in five weight classes, participated in some of the most compelling fights of his era, wooed fans on a mind-boggling scale and earned more money than all but one or two fighters in history.

"Oscar brought to the table a great personality and a great deal of talent, no question," Leonard said. "I think he passed the test in general. But it's very difficult to live up to any hype. It really is."

In this case, the hype was immense. With the gold medal came the moniker "The Golden Boy," a nickname that would prove prophetic when it came to business but gave him little room for error in the ring.

Some observers seem to forget how dominating he was in the first five years of his career, when he fought at 130, 135 and 140 pounds. At those weights, he went 23-0 with 20 knockouts by overwhelming his opponents with God-given talent, size (5-foot-11) and reach, unusual speed, and crushing power.

And remember: He succeeded even without the benefit of an established trainer, having worked with inexperienced Robert Alcazar before bouncing from one to trainer to another.

De La Hoya also never had much of a right hand. He's a natural lefty who fights right-handed, so his big punch was always his left hook. And, oh, what a left hook he had in the early days.

Rafael Ruelas, the tough, overachieving IBF lightweight champion, felt the power in that left hand in a high-profile 1995 bout outdoors at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. De La Hoya knocked down his L.A. rival twice with left hooks, the second one ending the fight in the second round and giving De La Hoya his first major title.

On that night, at that weight, De La Hoya was scary.

"Oscar made a world champion with more experience look silly," said Eric Gomez, De La Hoya's lifelong friend and current matchmaker for the fighter's promotional firm, Golden Boy Promotions Inc.

Among his other early victims: crafty John John Molina, against whom De La  Hoya first demonstrated that he could win a taxing brawl; Genaro Hernandez, one of the best technical boxers of his era; and Julio Cesar Chavez, his one-time idol whose face and aura were ripped apart by pinpoint blows.

Hoya first demonstrated that he could win a taxing brawl; Genaro Hernandez, one of the best technical boxers of his era; and Julio Cesar Chavez, his one-time idol whose face and aura were ripped apart by pinpoint blows.

De La Hoya was peaking. The teenyboppers swooned and the money started to roll in as he quickly became one of the sport's great attractions. To this point, in most eyes, he was living up to ever-intensifying hype.

"I think it was around this time that unreasonable expectations began to build," said  television analyst Larry Merchant, who has worked most of De La Hoya's big fights. "And it wasn't just his promoter [Bob Arum]; it was the whole boxing establishment. Everyone wanted him to become an all-time great, the next Sugar Ray Leonard -- or better.

television analyst Larry Merchant, who has worked most of De La Hoya's big fights. "And it wasn't just his promoter [Bob Arum]; it was the whole boxing establishment. Everyone wanted him to become an all-time great, the next Sugar Ray Leonard -- or better.

"I think that was laid on him because of his early success. Even Arum got caught up in it as he was carefully moving him through the various divisions."

“If I would've stayed at 140 or maybe 147, I think I could've accomplished a lot more. Who knows, maybe I would've been considered the greatest fighter on the planet. ”

— Oscar De La Hoya

At the same time, even when he was plowing his way through the lighter weights, De La Hoya had detractors.

The most common criticism: He was being coddled. His opponents were either past their primes (Chavez and later Pernell Whitaker, for example) or had moved up in weight to fight a bigger man (Jesse James Leija). That perception fostered a second nickname: "Chicken De La Hoya," the cold creation of veteran boxing writer Michael Katz.

Today, that label doesn't apply. In the end, De La Hoya fought almost everyone deemed worthy in and around his weight. He didn't match up well with speedy Shane Mosley, yet fought him twice. He was too small for Bernard Hopkins, yet took the chance in his most recent fight. And on May 6, having been out of the ring for 20 months, he faces wild slugger Ricardo Mayorga in Las Vegas.

Today, that label doesn't apply. In the end, De La Hoya fought almost everyone deemed worthy in and around his weight. He didn't match up well with speedy Shane Mosley, yet fought him twice. He was too small for Bernard Hopkins, yet took the chance in his most recent fight. And on May 6, having been out of the ring for 20 months, he faces wild slugger Ricardo Mayorga in Las Vegas.

In the hype leading up to the May 6 fight, Mayorga toyed with a live hen at his training camp in Miami to poke fun at De La Hoya but, by accepting a fight with the capable Nicaraguan, De La Hoya has proved again that he's no chicken.

Most observers now applaud the fact that De La Hoya has avoided few potential foes.

"He fought the best guys," trainer and ESPN television analyst Teddy Atlas said. "You have to give him credit for that. Even coming up, he fought guys like Molina, who you knew would give him trouble. … And in the last five, six years of his career, he took everyone on, even when it wasn't real smart from a management standpoint, [like] Mosley, for example. He took them on because of his pride, his confidence, the way he wanted to be thought of.

"You have to give him credit for that, especially because he didn't have to. He could've fought lesser guys and still got paid handsomely, but he didn't. He took risks."

And ultimately, he paid a price.

De La Hoya started his career 31-0 but is only 6-4 (between the ages of 25 and 31) since, which -- at a glance -- is hardly the record of a dominating champion.

Indeed, another common criticism is that he lost arguably the four biggest fights of his career: a controversial decision to Felix Trinidad at 147 pounds in 1999; two close decisions to Mosley, at 147 in 2000 and at 154 in 2003; and a ninth-round knockout against Hopkins at 160 in 2004.

Now, it's important to note that almost no one outside the Trinidad camp believes the Puerto Rican won that fight. De La Hoya picked him apart with his superior boxing skills for eight-plus rounds, appearing to be on his away to a one-sided decision.

Now, it's important to note that almost no one outside the Trinidad camp believes the Puerto Rican won that fight. De La Hoya picked him apart with his superior boxing skills for eight-plus rounds, appearing to be on his away to a one-sided decision.

Then, for still unclear reasons, De La Hoya did the inexplicable -- he ran. He bounced around the ring and away from Trinidad for three-plus rounds because he believed he was too far ahead on the cards to lose, as his corner told him, or because he tired badly -- or both.

Either way, it turned out to be the biggest regret of his career. The judges gave Trinidad a dubious majority decision, but De La Hoya lost sympathy because of his late tactics.

"I do regret it," De La Hoya said from his training camp in Puerto Rico in a telephone interview. "It was a fight I was winning easily and I should've won. If I would've stayed with the same game plan for 12 rounds, I probably even would've knocked him out. It was a no-brainer.

"I listened to my corner, and it was a mistake."

The Mosley fights were close. De La Hoya lost the first one to his then-unbeaten rival by a split decision in L.A. and the second by two points on all three cards in Las Vegas. No shame there, not against a fighter of Mosley's ability. Most observers point to Mosley's superior speed as the difference in the bouts.

The Mosley fights were close. De La Hoya lost the first one to his then-unbeaten rival by a split decision in L.A. and the second by two points on all three cards in Las Vegas. No shame there, not against a fighter of Mosley's ability. Most observers point to Mosley's superior speed as the difference in the bouts.

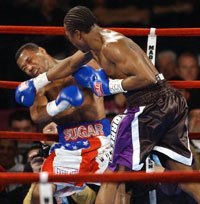

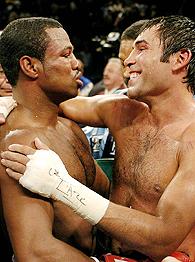

Although their first fight was close, Mosley, left, defeated De La Hoya for the second time on Sept. 13, 2003, this time by unanimous decision.

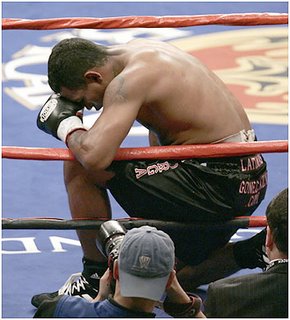

Then there was the Hopkins loss. De La Hoya's choice of opponent now looks misguided; even he admits Hopkins was too big. However, De La Hoya also lost favor by the way he lost. Hopkins was becoming increasingly dominant when he landed a left hook to the body that put De La Hoya down and he failed to get up.

Although their first fight was close, Mosley, left, defeated De La Hoya for the second time on Sept. 13, 2003, this time by unanimous decision.

“He fought the best guys. You have to give him credit for that. ... He could've fought lesser guys and still got paid handsomely, but he didn't. He took risks. ”

— ESPN boxing analyst Teddy Atlas, on Oscar De La Hoya

He lay on his side, grimacing in pain and pounding his fist on the canvas, but his legs wouldn't function.

Was it a paralyzing shot to the liver? Or was De La Hoya looking for a way out of the fight?

"I think the way he was beaten by Hopkins is a black mark," said trainer and former fighter Freddie Roach, who believes De La Hoya will be remembered as a great fighter. "Even though he was hit by a middleweight, it was still only a body shot. I've been hurt by body shots in my life and never experienced that.

Freddie Roach, who believes De La Hoya will be remembered as a great fighter. "Even though he was hit by a middleweight, it was still only a body shot. I've been hurt by body shots in my life and never experienced that.

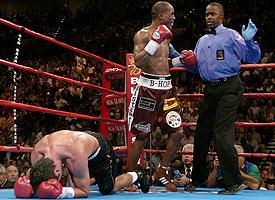

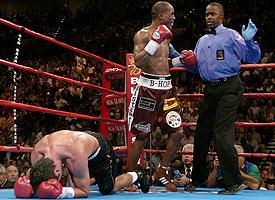

Bernard Hopkins, right, proved too big for De La Hoya, who moved up in weight to challenge for the middleweight title on Sept. 18, 2004. Hopkins scored a ninth-round KO.

"I think it was a hard body shot, but I kind of thought he could've gotten up. I guess that's easy for me to say."

Ironically, De La Hoya's two most memorable victories came at weights above 140. He believes his most significant accomplishment was rising from the canvas to knock down Ike Quartey in the 12th round and claim a split decision in 1999. Any doubts about De La Hoya's toughness evaporated during that final round.

"I think I showed my true heart that night. I'm proud of that moment," De La Hoya said.

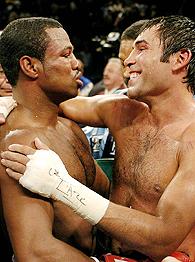

And his victory over hated rival Fernando Vargas in 2002 probably was his most spectacular win. That night, he fought like Hopkins, wearing Vargas down until finally taking him out in the 11th round.

Certainly, those triumphs, battles with more than 20 world champions and so many dominating performances at the lower weights -- not to mention his profound impact outside the ring -- give him unquestioned Hall of Fame credentials.

In what was a highly anticipated fight between 2 champions in there own respected divisions for

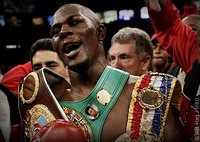

In what was a highly anticipated fight between 2 champions in there own respected divisions for  Regardless, at the end of this championship bout, Jermain seemed satisfied that he went to the

Regardless, at the end of this championship bout, Jermain seemed satisfied that he went to the  Conclusion: With Jermain Taylor's 3rd defense; though, not exactley a successful one, you could call this defense the Luck of the draw that kept him from relinquishing his belts. The verdict is still out on this young champon, is Jermain Taylor legit?

Conclusion: With Jermain Taylor's 3rd defense; though, not exactley a successful one, you could call this defense the Luck of the draw that kept him from relinquishing his belts. The verdict is still out on this young champon, is Jermain Taylor legit?